Just because I love handsewing, I chose to make a pair of undersleeves. Do I need a pair of undersleeves? Absolutely not! One day, maybe. Maybe I just wanted an excuse to procrastinate on my corset. It was a nice little project. If you're confused about what kind of undersleeves I'm talking about, here are a couple pictures. They would have been work with any type of sleeves that were open, and possibly shorter.

I pulled out leftover fabric from my dotted swiss dress. I thought I only had maybe a yard and a half. Man, it was more like 3! I've got a lot to work with. It's going to be like the dotted swiss that never dies. I love working with it, though; it irons really nicely, and just feels like a good quality. Just to recap, I bought it at Hancocks. The below originals are kind of textured, but not exactly dotted swiss.

All in all, they took about 4 hours of handsewing, or, in other words, 4 episodes of P+P. It cracks me up how much my sister loves that show.

From what I've seen, there are several different ways to do undersleeves. They can be completely detached, with either a drawstring or elastic at the top (yes, elastic!), or made longer and basted to the armscye of the dress itself. The undersleeve that doesn't attach is best worn with dresses whose sleeves are more tailored (as in the 1860s), vs. some of the 1850's open pagoda sleeves were occassionally slashed up very high, in which case a detached sleeve could potentially be too short.

Bonus: I had all the supplies already. Technically, I could have entered this into the Heirlooms and Heritage challenge, because I used buttons from my Great Great Grandma's stash (the same excuse as my lame drawers), but I chose not to. Hopefully, the mother-of-pearl doesn't look to dingy against the bright white fabric.

This may need to go into my pile of to-do tutorials, if I can revise it to basic squares.

Hello! I keep this blog so I can record my historical clothing research, sewing projects, and also be able to communicate what I am learning to my family and friends.

Monday, August 17, 2015

Monday, August 10, 2015

HSM #8: Heirlooms and Heritage

This has to be the lamest thing I've ever entered in the Historical Sew Monthly challenges. I had such fantastic plans that involved so much family history; what happened?

It turns out my embroidery skills are severely lacking. Plus, 18th century pockets are not at the top of the list of things I need before a certain event coming up. *Cries* I wanted to make them so badly, but embroidery is not my forte. I've tried it. It's okay.

So, here are my lame split drawers, using a bone button from my stash that came from great great Grandma.

What the item is: Split drawers

The Challenge: Heirlooms and Heritage

Fabric: 1 1/2 yards muslin

Pattern: from the Sewing Academy

Year: 1860's, ish.

Notions: Bone button, thread

How historically accurate is it? 80%, just a random number, but close enough to originals and definitely passes the "original cast recognizable".

Hours to complete: Around 6. More than it should have, but I handsewed a lot of it, just so I could watch North and South at the same time. :)

First worn: Not yet

Total cost: Under $5

Coming Up: Dog Leg Closure Tutorial, the easy way.

It turns out my embroidery skills are severely lacking. Plus, 18th century pockets are not at the top of the list of things I need before a certain event coming up. *Cries* I wanted to make them so badly, but embroidery is not my forte. I've tried it. It's okay.

So, here are my lame split drawers, using a bone button from my stash that came from great great Grandma.

There is a more period correct way to do laundry markings, but I am personally not picky about something like laundry markings.

I had planned on doing 3 tucks, but....something happened.

What the item is: Split drawers

The Challenge: Heirlooms and Heritage

Fabric: 1 1/2 yards muslin

Pattern: from the Sewing Academy

Year: 1860's, ish.

Notions: Bone button, thread

How historically accurate is it? 80%, just a random number, but close enough to originals and definitely passes the "original cast recognizable".

Hours to complete: Around 6. More than it should have, but I handsewed a lot of it, just so I could watch North and South at the same time. :)

First worn: Not yet

Total cost: Under $5

Coming Up: Dog Leg Closure Tutorial, the easy way.

Upcoming, Updated Projects

Here are how the voices in my head sound:

(Practical me) "I'm going to have to rip apart my old corset and start over."

(Sentimental me) "Nooooooooooooo!"

"Oh, you mean that old thing that has stretched into non-existence?"

"What do you mean, that old thing? It took me a hundred hours of fitting and was finished 6 months ago!"

I can't even wear it anymore, but letting it go was pretty sad. And now it lays in pieces on the table.

Not to worry, the Frankencorset's legacy lives on. The ripped apart pieces became a mock-up for little baby Frankencorset, which may get renamed into something nicer if the finished project turns out. (Frankencorset is not my own terminology, but I thought it was pretty darn creative!)

Here is the original list of problems which must be solved:

-A longer busk, as the first cut right into my gut and caused horrible stomach-aches straight after eating.

-One side modified, as two of the same side makes it sit crooked on my back.

-More taken in at the hips, so that the spring in the back is straight up and down.

-A more durable fabric, as one layer of twill wasn't enough.

-More boning in the front, and more flare in the angle they are sewn in. Straight up and down causes the boning to not sit right.

In my first stages of making it, I could never have forseen how it would not hold up. I thought it would at least last a year, but now it is basically able to lace closed.

I cut apart the old corset, and traced the outline into a pattern, and did as much flat-drafting as I felt comfortable with. I actually did make two of the same sides, even though that was on my list of things to do, because I thought that somewhere along the way, I might have taken in one side and not the other.

Not so.

However, the length on my first mockup is just right, and the shaping from the old one (which I love) is still the same. Overall, it's pretty big and can basically be laced closed, but for a first mockup, I'm pretty excited! The next step will be to take it in, and figure out where to adjust the one side for overall evenness.

(Practical me) "I'm going to have to rip apart my old corset and start over."

(Sentimental me) "Nooooooooooooo!"

"Oh, you mean that old thing that has stretched into non-existence?"

"What do you mean, that old thing? It took me a hundred hours of fitting and was finished 6 months ago!"

I can't even wear it anymore, but letting it go was pretty sad. And now it lays in pieces on the table.

Not to worry, the Frankencorset's legacy lives on. The ripped apart pieces became a mock-up for little baby Frankencorset, which may get renamed into something nicer if the finished project turns out. (Frankencorset is not my own terminology, but I thought it was pretty darn creative!)

Here is the original list of problems which must be solved:

-A longer busk, as the first cut right into my gut and caused horrible stomach-aches straight after eating.

-One side modified, as two of the same side makes it sit crooked on my back.

-More taken in at the hips, so that the spring in the back is straight up and down.

-A more durable fabric, as one layer of twill wasn't enough.

-More boning in the front, and more flare in the angle they are sewn in. Straight up and down causes the boning to not sit right.

In my first stages of making it, I could never have forseen how it would not hold up. I thought it would at least last a year, but now it is basically able to lace closed.

I cut apart the old corset, and traced the outline into a pattern, and did as much flat-drafting as I felt comfortable with. I actually did make two of the same sides, even though that was on my list of things to do, because I thought that somewhere along the way, I might have taken in one side and not the other.

Not so.

However, the length on my first mockup is just right, and the shaping from the old one (which I love) is still the same. Overall, it's pretty big and can basically be laced closed, but for a first mockup, I'm pretty excited! The next step will be to take it in, and figure out where to adjust the one side for overall evenness.

Thursday, August 6, 2015

Change of Plans

Even after making a long list of ideas for the August Heirlooms and Heritage challenge, I found something pretty cool. I took the Longfellow poem about my family's inn, and how he talk's about the landlord of the inn, who is a distant uncle of some sort.

'But first the Landlord will I trace;

Grave of aspect and attire;

A man of ancient pedigree,

A Justice of the peace was he,

Know in all Sudbuy as "The Squire."

Proud was he of his name and race,

Of old Sir William and Sir Hugh,

And in the parlor, full in view,

His coat of arms, well framed and glazed,

Upoon the wall in colors blazed;

He beareth gules upon his shield,

A chevron argent in the field,

with three wolf's heads, and for the crest

a Wyvern part-per-pale addressed

Upon a helmet barred; below

The scroll reads, 'By the name of Howe."

And over this, no longer bright,

Though glimmering with a latent light,

was hung the sword his grandsire bore

In the rebellious days of yore,

Down there at Concord in the fight.'

I had known nothing of a coat-of-arms, and using what he mentions in the poem, I found it! Just so you know, "gules" is an old English term for red. Chevron argent (a chevron, argent another word for silver); and I had no idea what a wyvern was! Of course, my fantasy-oriented sister knew; it's kind of like a dragon, but with only two legs and a barbed tail.

Just Googling Howe coat-of-arms brings up all kinds of things, but none matched the description. Except for this one:

'But first the Landlord will I trace;

Grave of aspect and attire;

A man of ancient pedigree,

A Justice of the peace was he,

Know in all Sudbuy as "The Squire."

Proud was he of his name and race,

Of old Sir William and Sir Hugh,

And in the parlor, full in view,

His coat of arms, well framed and glazed,

Upoon the wall in colors blazed;

He beareth gules upon his shield,

A chevron argent in the field,

with three wolf's heads, and for the crest

a Wyvern part-per-pale addressed

Upon a helmet barred; below

The scroll reads, 'By the name of Howe."

And over this, no longer bright,

Though glimmering with a latent light,

was hung the sword his grandsire bore

In the rebellious days of yore,

Down there at Concord in the fight.'

I had known nothing of a coat-of-arms, and using what he mentions in the poem, I found it! Just so you know, "gules" is an old English term for red. Chevron argent (a chevron, argent another word for silver); and I had no idea what a wyvern was! Of course, my fantasy-oriented sister knew; it's kind of like a dragon, but with only two legs and a barbed tail.

Just Googling Howe coat-of-arms brings up all kinds of things, but none matched the description. Except for this one:

Notice the Wyvern, with the barbed tail, the red crest, the three wolves, and the silver chevron. Bingo! By the by, the scroll at the bottom says Howe.

Apparently, in 1871, some ancestry geek wanted to have a Howe get-together, celebrating the Howes. There is actually a book available that he wrote about the entire gathering. The only reason I say he was a ancestry geek is because he wrote a song. Come on, no one writes a song unless they're obsessed. The first verse is as follows:

You meet today to celebrate with fillial heart and brow,

as children of one family, the dear old name of Howe.

Brothers and sisters by that name you hold in reverence dear,

how fitting you should set apart, this day for friendly cheer!

No joke.

I got it into my head that I wanted to put this family crest on something, and the only item I could come up with is a pair of 18th century pockets; the type that tie around your waist. Like this:

The main reason being, it's one of the few garments that is basically always embroidered. Flowers seem to be the most common, but I'm okay with taking a few liberties. I already have the pattern from Patterns of Fashion 1, and some heavy mystery cotton that might be canvas, or duck.

The only problem is: I'm not really into embroidery. My sister is, but I can't make up my mind if I want to push through and do it. I would love to have something with the coat-of-arms, but it's kind of a big undertaking for someone who isn't in love with embroidery. I don't know. I may just skip this challenge, or revisit it for the do-over challenge in December.

Wednesday, July 29, 2015

Historical Sew Monthly #7: Accesories

After receiving the fabric I bought online, I set to work right away. Here is my post that I used for inspiration.

A friend of mine had already drafted a wonderful pattern for a drawn bonnet, so I didn't have to do any kind of mock-up. It actually went together really well, but I did have a lot of trouble with the white dupioni lining completely fraying apart, especially on the grain for some reason. The back seam where the crown piece attaches was the worst.

I did, from experience, know that the crown piece was just a little bit small, so I went ahead and enlarged it just a little to accommodate more seam allowances. I also had to sew that bit by hand, because of how badly the lining had frayed. Next time, I will just spend the extra money to use silk taffeta; the quality has proved to be amazing and completely worth it. Actually, I had to sew it twice because the first time I winged it, and the crown didn't line up. The second time I drew up the gathers and actually measured *gasp*! I'm more of a measure once, cut twice kind of seamstress.

The plastic boning is a little bit funny; first, it wouldn't stop coiling back into it's original roll, then I pinned it inside out to sew the crown on and left it overnight. It completely lost it's shape, but now it's pretty pliable. Goes to show how flimsy plastic boning is, especially to support a garment.

One secret to plastic boning: if you use the hand crank on the side of your sewing machine, you can stitch right through it. It makes your needle dull, but it's pretty important to be able to sew them in for this particular project, otherwise the fabric wouldn't stay gathered up right to the edge.

Now, I'm trying to decide if I want flowers on the inside of the brim, or not.

What the item is: Drawn Bonnet

The Challenge: Accessorise

Fabric: Silk taffeta, lined with dupioni

Pattern: Made from a friend's, which she drafted herself

Year: 1850-1860

Notions: Thread, plastic boning, faux flowers, ribbon, lace

How historically accurate is it? Not particularly; with the plastic boning, it's not really shapeable. I'm going with 40%. Not historically accurate materials, except for the main fabric, but it looks accurate enough. I was hoping it would turn out a little higher at the top, like in 1860's fashion plates, but the outcome is more of in the shape of 1840s and 50s round.

Hours to complete: 12-13

First worn: Not yet

Total cost: Around $35

A friend of mine had already drafted a wonderful pattern for a drawn bonnet, so I didn't have to do any kind of mock-up. It actually went together really well, but I did have a lot of trouble with the white dupioni lining completely fraying apart, especially on the grain for some reason. The back seam where the crown piece attaches was the worst.

I did, from experience, know that the crown piece was just a little bit small, so I went ahead and enlarged it just a little to accommodate more seam allowances. I also had to sew that bit by hand, because of how badly the lining had frayed. Next time, I will just spend the extra money to use silk taffeta; the quality has proved to be amazing and completely worth it. Actually, I had to sew it twice because the first time I winged it, and the crown didn't line up. The second time I drew up the gathers and actually measured *gasp*! I'm more of a measure once, cut twice kind of seamstress.

The plastic boning is a little bit funny; first, it wouldn't stop coiling back into it's original roll, then I pinned it inside out to sew the crown on and left it overnight. It completely lost it's shape, but now it's pretty pliable. Goes to show how flimsy plastic boning is, especially to support a garment.

It looks like a lampshade at this point.

One secret to plastic boning: if you use the hand crank on the side of your sewing machine, you can stitch right through it. It makes your needle dull, but it's pretty important to be able to sew them in for this particular project, otherwise the fabric wouldn't stay gathered up right to the edge.

The crown piece probably could have used some buckram to help it lay more flat.

Now, I'm trying to decide if I want flowers on the inside of the brim, or not.

What the item is: Drawn Bonnet

The Challenge: Accessorise

Fabric: Silk taffeta, lined with dupioni

Pattern: Made from a friend's, which she drafted herself

Year: 1850-1860

Notions: Thread, plastic boning, faux flowers, ribbon, lace

How historically accurate is it? Not particularly; with the plastic boning, it's not really shapeable. I'm going with 40%. Not historically accurate materials, except for the main fabric, but it looks accurate enough. I was hoping it would turn out a little higher at the top, like in 1860's fashion plates, but the outcome is more of in the shape of 1840s and 50s round.

Hours to complete: 12-13

First worn: Not yet

Total cost: Around $35

Thursday, July 23, 2015

Historical Sew Monthly Challenge #8: Heirlooms and Heritage Inspiration

This month's sewing challenge guidelines is "sew something that reflects on family heritage, or use an heirloom, or make a new heirloom." Or something along those lines. My family is rich with history, and also in stories and heritage. No heirlooms to speak of, but what to pick? Who to choose? How do I make an item that has to do with any of this?

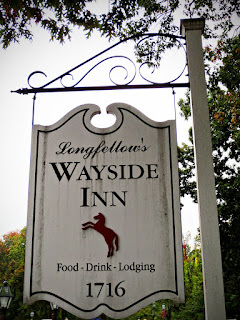

My great great great great great great great great great (9 greats) grandfather's name was Samuel Howe. He was born in Massachusetts in 1642, and in 1702 he deeded some property to his son David. I am a direct descendant of Samuel's other son Nehemiah, but David went on to build the Wayside Inn. The Wayside Inn is the current oldest inn in America, and is still open to the public. In 1862, Henry Longfellow, the famous poet, visited the Wayside Inn and wrote a series of poems about the inn and it's visitors. Someday, I hope to see the inn for myself.

Even though Howe is part of my family's name, I have found no evidence that I am in any way related to Elias Howe, the inventor of the sewing machine. Pity, that would have been nice for the upcoming sewing challenge.

I am also a descendant of Benjamin Russell. With his partner, Caleb Purrington, he painted what is thought to be the longest painting in the world, called Whaling Voyage Round the World. It is 8 1/2 feet tall, and 1,275 feet long! That is comparable to the Empire State building, or the Statue of Liberty stacked up 4 times!

Jemima Sawtelle's (or Sartelle) story is pretty interesting. In 1755, she was married and had 5 sons and 2 daughters. I am unsure of the daughter's age, but I'm guessing they were older than the sons. The sons were all under 8 years old. This was also the year that France and Britain were warring over the possession of Canada. Indians came down from Canada and kidnapped her and her children and took her with them to Canada. Her husband Caleb was scalped. Eventually, after being separated from her sons for years, she was sold to a kind family who helped reunite her with her family, and they moved back to the homestead they had left behind. She also remarried an Indian.

Even with all this information, what am I going to do with it? How am I supposed to sew something that might reflect on any of these stories? Ideas are much appreciated, but my brain is somewhere along the lines of farming. I come from a long line of farmers, which is almost double irony because my dad is a Farmers Insurance agent. Go figure.

My great great great great great great great great great (9 greats) grandfather's name was Samuel Howe. He was born in Massachusetts in 1642, and in 1702 he deeded some property to his son David. I am a direct descendant of Samuel's other son Nehemiah, but David went on to build the Wayside Inn. The Wayside Inn is the current oldest inn in America, and is still open to the public. In 1862, Henry Longfellow, the famous poet, visited the Wayside Inn and wrote a series of poems about the inn and it's visitors. Someday, I hope to see the inn for myself.

Grist Mill, which is part of the Wayside Inn estate.

Even though Howe is part of my family's name, I have found no evidence that I am in any way related to Elias Howe, the inventor of the sewing machine. Pity, that would have been nice for the upcoming sewing challenge.

I am also a descendant of Benjamin Russell. With his partner, Caleb Purrington, he painted what is thought to be the longest painting in the world, called Whaling Voyage Round the World. It is 8 1/2 feet tall, and 1,275 feet long! That is comparable to the Empire State building, or the Statue of Liberty stacked up 4 times!

Just a small snippet of the panorama

Jemima Sawtelle's (or Sartelle) story is pretty interesting. In 1755, she was married and had 5 sons and 2 daughters. I am unsure of the daughter's age, but I'm guessing they were older than the sons. The sons were all under 8 years old. This was also the year that France and Britain were warring over the possession of Canada. Indians came down from Canada and kidnapped her and her children and took her with them to Canada. Her husband Caleb was scalped. Eventually, after being separated from her sons for years, she was sold to a kind family who helped reunite her with her family, and they moved back to the homestead they had left behind. She also remarried an Indian.

Even with all this information, what am I going to do with it? How am I supposed to sew something that might reflect on any of these stories? Ideas are much appreciated, but my brain is somewhere along the lines of farming. I come from a long line of farmers, which is almost double irony because my dad is a Farmers Insurance agent. Go figure.

Monday, July 20, 2015

How to Scale Up a Diagram

Since I received Janet Arnold's books for my birthday, I've started scaling up some of the patterns so I can actually use them. They're all on a diagram, and each tiny square = 1''. Of course, I doubt I'll ever get around to making some of these things, but I like to hang on to the finished patterns.

Many ladies like to go to a print shop and print the patterns up to scale, but I've been doing mine at home. It takes a bit of time, but not a lot, and it isn't that hard. The books themselves suggest to draw out a grid on paper and then transfer it, but I tried that and it takes forever just to draw out the grid! I think I spent an hour using that method just for the front bodice piece. The method below is my own.

You will need:

-A fairly large quilting mat.

-A long ruler; I use a quilting ruler that is 18''x3''. A yardstick could potentially work, but a normal 12'' ruler would be too short.

-A roll of see-through plastic tablecloth; the kind that is used for parties and cut to the table size, then thrown away afterwords. It is imperative that it is see-through, that is what makes this process so easy!*

-A couple weights, or anything heavy that happens to be nearby (a candle, the Bible, a mug of coffee, which wasn't a good idea....)

-A permanent marker, and a normal old pen

-The pattern you wish to scale up!

*Now I am going to talk about how much I love this stuff. I bought a big roll at Zurchers for around $10, and it is the best thing ever! Not only can it be manipulated like fabric on a dress form, but it is see-through, which is a great advantage in doing scaling work. It also stores better than paper, which creases and rips. This doesn't really rip, but it can stretch if pulled too much. I actually tried to sew with it like a mock up, but the feed-dogs on my machine didn't like that.

Before I begin, there are certain pieces which I don't bother with. Usually, this means skirts, especially if they are just rectangles sewn together. Even if it has a train or the like, I know that it probably wouldn't be the right length anyway, so I just go ahead and mark the circumference and occasionally length of the skirt somewhere on one of the other pattern pieces. Complicated draping on bustle skirts might be the main exception, or some of the really fitted skirts in the 2nd volume.

To start, spread out your plastic roll onto the mat and put a couple weights on the corners. Match up the edge of the plastic so that it doesn't butt up directly to that line but a little past it.

If there are any straight lines on the grain of the fabric, like center front or back, start there and use your ruler to keep it neat. You'll work off of this line. Use the normal pen, because later we'll use the permanent marker to darken the final lines. The particular pattern I'm scaling today is a 1770-1780 bodice. Most of the dress in the 1700's are pretty easy, because the very front is straight. However, the front on this one isn't on the grain, so I'm going to start on the bottom.

To draw the rest of the confusing curves, there are a couple different ways to do it. 1, mark it slowly square by square, or 2, mark dots every so often and connect them with a smooth curve. Below, I'm doing a little of both at the same time.

I usually pay attention on the grid to where the lines go through the square. Mentally, I'll mark it either as 1/4'', a hair to either side of that, or right from corner to corner, etc. Take advantage of the little dots within each square inch on the mat.

Here, I've come to where I'd rather not mark out every single line, so carefully counting out the squares I made a reference point at center front. I'm just going to 'wing it', so to speak. Isn't my way of drafting great? Maybe that's why I have to spend so much time mocking up...

On all the lines that are straight, but aren't on the grain, I like to work completely around it until the end, and then use the ruler to connect them.

Remember, the Janet Arnold patterns don't have seam allowances included, so when cutting out the pattern to store, allow a couple inches all the way around for some flat drafting. Of course, I should take my own advice, since I messed up and there wasn't any on the side seam in the end. Don't forget to also add grain arrows to keep it all neat! To store them, pin all the pieces together and date them so they don't get mixed up.

Many ladies like to go to a print shop and print the patterns up to scale, but I've been doing mine at home. It takes a bit of time, but not a lot, and it isn't that hard. The books themselves suggest to draw out a grid on paper and then transfer it, but I tried that and it takes forever just to draw out the grid! I think I spent an hour using that method just for the front bodice piece. The method below is my own.

You will need:

-A fairly large quilting mat.

-A long ruler; I use a quilting ruler that is 18''x3''. A yardstick could potentially work, but a normal 12'' ruler would be too short.

-A roll of see-through plastic tablecloth; the kind that is used for parties and cut to the table size, then thrown away afterwords. It is imperative that it is see-through, that is what makes this process so easy!*

-A couple weights, or anything heavy that happens to be nearby (a candle, the Bible, a mug of coffee, which wasn't a good idea....)

-A permanent marker, and a normal old pen

-The pattern you wish to scale up!

My adorable dog, who likes to supervise.

*Now I am going to talk about how much I love this stuff. I bought a big roll at Zurchers for around $10, and it is the best thing ever! Not only can it be manipulated like fabric on a dress form, but it is see-through, which is a great advantage in doing scaling work. It also stores better than paper, which creases and rips. This doesn't really rip, but it can stretch if pulled too much. I actually tried to sew with it like a mock up, but the feed-dogs on my machine didn't like that.

Before I begin, there are certain pieces which I don't bother with. Usually, this means skirts, especially if they are just rectangles sewn together. Even if it has a train or the like, I know that it probably wouldn't be the right length anyway, so I just go ahead and mark the circumference and occasionally length of the skirt somewhere on one of the other pattern pieces. Complicated draping on bustle skirts might be the main exception, or some of the really fitted skirts in the 2nd volume.

To start, spread out your plastic roll onto the mat and put a couple weights on the corners. Match up the edge of the plastic so that it doesn't butt up directly to that line but a little past it.

If there are any straight lines on the grain of the fabric, like center front or back, start there and use your ruler to keep it neat. You'll work off of this line. Use the normal pen, because later we'll use the permanent marker to darken the final lines. The particular pattern I'm scaling today is a 1770-1780 bodice. Most of the dress in the 1700's are pretty easy, because the very front is straight. However, the front on this one isn't on the grain, so I'm going to start on the bottom.

To draw the rest of the confusing curves, there are a couple different ways to do it. 1, mark it slowly square by square, or 2, mark dots every so often and connect them with a smooth curve. Below, I'm doing a little of both at the same time.

I usually pay attention on the grid to where the lines go through the square. Mentally, I'll mark it either as 1/4'', a hair to either side of that, or right from corner to corner, etc. Take advantage of the little dots within each square inch on the mat.

Here, I've come to where I'd rather not mark out every single line, so carefully counting out the squares I made a reference point at center front. I'm just going to 'wing it', so to speak. Isn't my way of drafting great? Maybe that's why I have to spend so much time mocking up...

Good enough, says the sewing demon within me.

On all the lines that are straight, but aren't on the grain, I like to work completely around it until the end, and then use the ruler to connect them.

Outline the finished product in permanent marker so that any lines that you may have had to fiddle with to get straight don't mess you up later.

Remember, the Janet Arnold patterns don't have seam allowances included, so when cutting out the pattern to store, allow a couple inches all the way around for some flat drafting. Of course, I should take my own advice, since I messed up and there wasn't any on the side seam in the end. Don't forget to also add grain arrows to keep it all neat! To store them, pin all the pieces together and date them so they don't get mixed up.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)